What is a Basking Shark?

The basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus) is the world’s second-largest fish species, reaching lengths of 26 feet on average with some individuals exceeding 40 feet. Despite their massive size, basking sharks are completely harmless filter feeders that consume only plankton, filtering up to 2,000 tons of seawater per hour through their enormous gaping mouths. They get their name from their habit of swimming slowly at the ocean’s surface, appearing to “bask” in the sun while actually feeding on plankton-rich surface waters.

Swimming just beneath the surface with its massive mouth agape, the basking shark presents one of nature’s most awe-inspiring yet misunderstood spectacles. These gentle giants glide through temperate oceans worldwide, filtering microscopic plankton from thousands of tons of seawater daily. Despite being the second-largest fish on Earth—surpassed only by whale sharks—basking sharks pose absolutely no threat to humans and rarely make headlines despite their extraordinary biology.

From their mysterious deep-water migrations to their exceptionally long gestation periods, basking sharks continue to fascinate marine biologists and ocean enthusiasts alike. This comprehensive guide explores everything you need to know about Cetorhinus maximus, from their impressive physical characteristics and unique filter-feeding mechanism to their endangered conservation status and where you might encounter these magnificent creatures in the wild.Whether you’re a marine biology student, an ocean conservation advocate, or simply curious about one of the ocean’s most remarkable inhabitants, this complete guide will answer all your questions about the basking shark’s size, diet, habitat, behavior, and role in marine ecosystems.

What is a Basking Shark? Definition and Taxonomy

The basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus) is a species of shark belonging to the family Cetorhinidae—a family in which it is the only living member. This makes the basking shark taxonomically unique among modern sharks, with no close living relatives.

Scientific Classification

Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Chondrichthyes (cartilaginous fish) Order: Lamniformes (mackerel sharks) Family: Cetorhinidae Genus: Cetorhinus Species: C. maximus

The scientific name Cetorhinus maximus derives from Greek and Latin roots that perfectly describe this massive creature. “Cetorhinus” combines the Greek words “ketos” (meaning whale or sea monster) and “rhinos” (meaning nose), while “maximus” is Latin for “greatest” or “largest.” Together, the name translates roughly to “great whale-nosed shark,” referencing both the animal’s enormous size and its distinctive snout.

Second-Largest Fish Designation

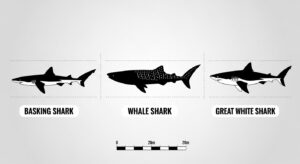

The basking shark holds the prestigious title of the world’s second-largest fish species, claiming this position behind only the whale shark (Rhincodon typus). While whale sharks can reach lengths exceeding 60 feet, basking sharks typically max out around 30-40 feet, though both species share the distinction of being filter-feeding giants that subsist entirely on microscopic prey.

This “second-largest” designation has remained consistent throughout scientific history, with the basking shark significantly outsize every other fish species except its tropical counterpart, the whale shark. No bony fish, predatory shark, or ray comes close to matching the basking shark’s impressive dimensions.

Evolutionary History

The basking shark lineage extends back millions of years. The oldest known relative of modern basking sharks is Keasius, an extinct genus that lived approximately 66 million years ago during the late Cretaceous period. Fossil evidence traces the basking shark family back 35-29 million years to the Cenozoic era, with the modern basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus) appearing in the fossil record about 23 million years ago during the late Miocene epoch.

This ancient lineage demonstrates the basking shark’s successful evolutionary adaptation to filter feeding in temperate oceans—a niche it has occupied for tens of millions of years.

Common Names Around the World

Beyond “basking shark,” this species is known by numerous regional names that reflect its distinctive appearance and behavior:

- Bone shark – Referencing the skeleton-like appearance of decomposing carcasses

- Elephant shark – Used in Italy, describing the large, trunk-like snout

- Sailfish or Sunfish – Highlighting the prominent dorsal fin and surface-swimming behavior

- Hoe-mother – A traditional name in some English-speaking regions

In other languages, the basking shark goes by names like “brugde” (Danish), “an liamhán gréine” (Irish, meaning “the great sun fish”), “büyük camgöz” (Turkish), and “cação-peregrino” (Portuguese, meaning “pilgrim shark”).

Basking Shark Size and Physical Characteristics

The basking shark’s massive size constitutes one of its most defining characteristics, making it instantly recognizable even to casual observers.

Average and Maximum Size

Average adult length: 23-28 feet (7-8.5 meters)

Typical length: 26 feet (7.9 meters)

Maximum recorded length: 40.3 feet (12.27 meters)

The largest confirmed basking shark on record measured 40.3 feet (12.27 meters) and was captured in a herring net in the Bay of Fundy, Canada, in 1851. Historical reports claim even larger specimens—including estimates of individuals reaching 45-46 feet—but these visual assessments lack scientific verification. Modern research suggests that basking sharks exceeding 33 feet (10 meters) are exceptionally rare, and individuals larger than this represent the extreme upper limit of the species’ growth potential.

Sexual dimorphism appears minimal in basking sharks, with males and females reaching similar maximum sizes, though males typically mature at smaller sizes than females.

Weight and Mass

Average adult weight: 8,500-10,000 pounds (3,900-4,650 kg) Typical weight: 9,300 pounds (4,200 kg) Maximum recorded weight: Estimated 36,000 pounds (16,000 kg)

The weight of basking sharks correlates directly with their length, though individual body condition and liver size significantly impact total mass. The enormous liver alone—which can constitute 25% of total body weight—adds 2,000-2,500 pounds (900-1,100 kg) to the shark’s mass. This means a large basking shark may carry a liver containing nearly 500 gallons of oil, historically making them prime targets for commercial hunting.

To put this in perspective, an average adult basking shark weighs approximately five times as much as an average great white shark, despite the great white’s fearsome reputation.

Size Comparison Table

| Species | Average Length | Maximum Length | Average Weight | Maximum Weight |

| Basking Shark | 26 ft (7.9 m) | 40 ft (12.3 m) | 9,300 lbs (4,200 kg) | 36,000 lbs (16,000 kg) |

| Whale Shark | 40 ft (12 m) | 60+ ft (18+ m) | 20,000 lbs (9,000 kg) | 47,000 lbs (21,000 kg) |

| Great White Shark | 15 ft (4.6 m) | 20 ft (6 m) | 2,000 lbs (900 kg) | 5,000 lbs (2,300 kg) |

| Tiger Shark | 13 ft (4 m) | 18 ft (5.5 m) | 850 lbs (385 kg) | 2,000 lbs (900 kg) |

This comparison clearly illustrates the basking shark’s exceptional size—nearly double the length and five times the weight of formidable predatory species like the great white shark.

Distinctive Physical Features

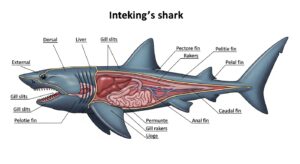

Enormous Gill Slits

The most immediately recognizable feature of basking sharks is their extraordinarily large gill slits, which extend almost completely around the head from top to bottom. These five massive gill openings can measure up to 3 feet (1 meter) in length, nearly encircling the shark’s entire circumference just behind the head. This adaptation maximizes water flow over the gills, essential for their filter-feeding lifestyle.

Massive Gaping Mouth

When feeding, a basking shark’s mouth can open up to 3 feet (1 meter) wide—wide enough for a small adult human to fit inside (though this would never happen, as basking sharks avoid large objects). The cavernous mouth lacks the fearsome teeth of predatory sharks, instead featuring hundreds of tiny, non-functional teeth and specialized gill rakers for filtering plankton.

Prominent Dorsal Fin

The basking shark’s tall, triangular dorsal fin frequently breaks the water’s surface as the shark swims, making it easily visible from boats and shore. In large individuals, this fin can measure over 3 feet (1 meter) in height and may flop to one side when exposed above water due to its flexible cartilaginous structure.

Conical Pointed Snout

Unlike the broad, flattened heads of some sharks, basking sharks possess a distinctly conical, pointed snout that appears more prominent in younger individuals. This snout shape contributes to the shark’s streamlined profile despite its massive bulk.

Large Liver and Body Shape

The basking shark’s enormous liver, which comprises up to 25% of its total body weight, runs through the entire length of the abdominal cavity. This oil-rich organ serves dual purposes: providing buoyancy to keep the shark afloat without expending energy, and storing long-term energy reserves. The liver’s high squalene content (a low-density hydrocarbon oil) gives the shark near-neutral buoyancy, allowing it to maintain depth with minimal swimming effort.

Coloration and Skin

Basking sharks display variable coloration, typically ranging from dark gray-brown to nearly black on their dorsal (top) surface, gradually fading to a paler gray or dull white on their ventral (bottom) surface. Some individuals exhibit mottled patterns or patches of lighter coloration.

The skin itself is rough and highly textured, covered in tiny tooth-like scales called placoid scales (dermal denticles) and coated in a thick mucus layer. This rough texture can cause abrasions to divers who make contact, despite the shark’s gentle nature. Many basking sharks display numerous scars, likely from encounters with parasitic lampreys or cookiecutter sharks.

Crescent-Shaped Tail

The basking shark’s caudal (tail) fin is distinctly lunate (crescent-shaped) with a strong lateral keel along the caudal peduncle (the area where the tail connects to the body). This tail shape, while less powerful than that of fast-swimming predatory sharks, provides efficient propulsion for the basking shark’s slow, steady swimming style.

What Do Basking Sharks Eat? Diet and Feeding Behavior

Despite their enormous size and shark lineage, basking sharks are among the ocean’s gentlest giants, subsisting entirely on microscopic prey through highly specialized filter feeding.

Filter-Feeding Mechanism Explained

Basking sharks are one of only three shark species that feed exclusively through filter feeding—the others being whale sharks and the rare megamouth shark. This feeding strategy involves swimming slowly through plankton-rich waters with their enormous mouths wide open, passively filtering microscopic organisms from the water passing through their gills.

The mechanics of basking shark filter feeding are remarkable in their simplicity and efficiency:

- Mouth Opening: The shark opens its massive mouth to approximately 3 feet (1 meter) in diameter while swimming at speeds of 2-3 mph (3-5 km/h).

- Water Intake: As the shark swims forward, water flows into the mouth and across the gills at an astonishing rate of up to 2,000 tons per hour (approximately 500,000 gallons or 1.9 million liters).

- Filtration: As water passes over the gills and exits through the gill slits, specialized structures called gill rakers trap plankton while allowing water to flow through.

- Swallowing: After filtering for approximately one minute, the shark closes its mouth to swallow the accumulated plankton, then reopens to continue feeding.

- Continuous Feeding: During peak feeding periods, basking sharks may feed for several hours continuously, processing millions of gallons of water to extract sufficient nutrition.

Gill Rakers: The Filtering Apparatus

The key to basking shark filter feeding lies in their highly developed gill rakers—dark, bristle-like structures that line the interior of each gill arch. These gill rakers act like a fine sieve, creating a filtering mesh that captures plankton particles while permitting water to flow freely through.

Each gill raker measures only a few millimeters in length but occurs in extraordinary numbers, creating an efficient filtering system capable of extracting even the smallest zooplankton from seawater. The gill rakers can trap organisms as small as a few millimeters, ensuring that virtually all nutritious plankton passing through is retained.

Interestingly, basking sharks may shed their gill rakers seasonally, potentially during winter months when plankton abundance decreases. This has led some researchers to hypothesize that basking sharks might fast during periods of low plankton availability, though this theory remains debated among scientists.

Plankton Diet:

The basking shark’s diet consists entirely of zooplankton—microscopic to small animals that drift with ocean currents. The primary components include:

Copepods: Tiny crustaceans measuring 1-5 millimeters that represent the most abundant zooplankton in many temperate waters. Copepods form the bulk of the basking shark’s diet in most regions.

Barnacle larvae: During certain seasons, the larvae of barnacles and other crustaceans become abundant in surface waters, providing rich feeding opportunities.

Decapod larvae: The larval stages of crabs, lobsters, and shrimp drift in the plankton before settling to the seafloor, offering protein-rich nutrition.

Fish eggs and larvae: When fish species spawn en masse, their eggs and newly hatched larvae create dense plankton clouds that attract basking sharks.

Shrimp and krill: Small shrimp-like creatures and krill (small crustaceans) supplement the diet when abundant.

Other zooplankton: The diet includes various other small organisms such as pteropods (sea butterflies), chaetognaths (arrow worms), and other drifting invertebrates.

Basking sharks show no dietary preference for phytoplankton (microscopic plants/algae), focusing exclusively on animal-based zooplankton for protein and fat content.

Daily Food Consumption

To sustain their massive bodies, basking sharks must consume extraordinary quantities of plankton daily. Estimates suggest that an adult basking shark needs to filter and consume approximately 2,000 pounds (900 kg) of zooplankton daily to meet its metabolic requirements.

This massive intake is made possible by the shark’s exceptional water filtration rate. Processing up to 2,000 tons of water per hour means a basking shark can filter through approximately 4 million pounds (1,814 metric tons) of water during extended feeding sessions. Given that plankton concentrations typically range from 1-10 grams per cubic meter of water, the shark must process enormous volumes to extract sufficient nutrition.

The feeding efficiency varies based on plankton density. In plankton-rich blooms, basking sharks can meet their nutritional needs in a few hours of feeding. In areas with lower plankton concentrations, they may need to feed throughout daylight hours.

Feeding Behavior and Patterns

Basking sharks exhibit predictable feeding behaviors tied to plankton distribution:

Surface Feeding: The characteristic “basking” behavior—swimming slowly at or just below the surface with mouth open—occurs when plankton concentrates in warm, sunlit surface waters. Phytoplankton (which feeds the zooplankton) requires sunlight for photosynthesis, creating plankton blooms in surface layers during sunny conditions.

Seasonal Patterns: Feeding activity peaks during spring and summer months (April through August in the Northern Hemisphere) when plankton blooms are most abundant in temperate coastal waters. During these months, basking sharks migrate to productive coastal areas.

Group Feeding: While typically solitary, basking sharks sometimes aggregate in groups of 50-100 (or rarely more) when encountering exceptionally dense plankton patches. These feeding aggregations allow multiple sharks to exploit the same food source.

Depth Variation: Although famous for surface feeding, basking sharks also feed at depth. Tagged individuals have been recorded diving to depths exceeding 3,000 feet (900 meters), where they feed on deep-water zooplankton, particularly during winter months when surface plankton becomes scarce.

Comparison to Other Filter-Feeding Sharks

The three filter-feeding shark species employ slightly different strategies:

Basking Shark: Passive ram filter feeder—swims forward with mouth open, relying entirely on forward motion to push water through gill rakers. Prefers temperate, cooler waters.

Whale Shark: Active suction feeder—can create suction to draw water into the mouth in addition to ram feeding. Prefers tropical, warm waters. Feeds on similar plankton but also consumes larger prey like small fish.

Megamouth Shark: Deep-water filter feeder—possesses bioluminescent tissue that may attract plankton. Rarely observed, least understood of the three.

Among these three species, basking sharks are unique in their preference for cold to temperate waters and their exclusively passive ram feeding approach.

Where Basking Sharks Live

Basking sharks are highly migratory, cosmopolitan species found in temperate and boreal oceans throughout both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres.

Global Distribution

Basking sharks inhabit all of the world’s major temperate oceans, demonstrating a truly global distribution pattern that spans multiple continents and ocean basins.

Northern Atlantic Ocean:

- Coastal waters of the United Kingdom and Ireland (especially Scotland)

- North Sea

- Norwegian Sea

- Iceland

- Greenland

- Canadian Atlantic coast (Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Bay of Fundy)

- U.S. East Coast (New England southward to North Carolina)

- Mediterranean Sea (though rare and possibly extirpated from some regions)

Northern Pacific Ocean:

- Alaska

- British Columbia, Canada

- U.S. West Coast (Washington, Oregon, California—particularly Monterey Bay)

- Japan

- Korea

- Northern China

Southern Oceans:

- South Africa

- Southern Australia

- Tasmania

- New Zealand

- Chile

- Argentina

- Southern Brazil

Other Regions:

- Indian Ocean (less common)

- Sub-Antarctic waters

This distribution pattern demonstrates the basking shark’s preference for cool to temperate waters, typically ranging from 46-58°F (8-14°C), though they can tolerate temperatures from 32-75°F (0-24°C).

Preferred Habitat Characteristics

Temperate Coastal Waters: Basking sharks show a strong preference for continental shelf waters and coastal zones where plankton productivity is highest. They frequently occur in waters 30-600 feet (10-200 meters) deep, particularly around areas of upwelling where nutrient-rich deep water rises to the surface, fueling plankton blooms.

Offshore and Pelagic Zones: While often sighted near coasts, basking sharks also inhabit open ocean (pelagic) environments during migrations. Tagged sharks have been tracked crossing entire ocean basins, traveling thousands of miles between coastal feeding areas.

Depth Range: Basking sharks exhibit remarkable depth flexibility:

- Surface waters (0-30 feet/0-10 meters) during feeding

- Mid-water (100-500 feet/30-150 meters) during transit

- Deep water (up to 3,000+ feet/900+ meters) during winter months

This depth versatility allows basking sharks to access plankton resources at various ocean levels and potentially escape extreme surface temperatures.

Seasonal Movements and Migration

Basking sharks are highly migratory, with seasonal movement patterns tied to plankton availability and water temperature.

Spring and Summer (April-August): During warmer months, basking sharks move into shallow coastal waters in temperate regions where spring and summer plankton blooms provide abundant food. This is when sightings peak in areas like:

- Scottish Inner Hebrides

- Southwest England (Cornwall)

- West Coast of Ireland

- California’s Monterey Bay

- Canadian Maritime provinces

Autumn and Winter (September-March): As plankton abundance declines and water temperatures drop, basking sharks largely disappear from coastal areas. For decades, scientists debated whether these sharks hibernated in deep-water refuges or migrated to different regions.

Modern tagging technology has revealed the truth: basking sharks remain active year-round, diving to depths of 600-3,000 feet (200-900 meters) where they feed on deep-water zooplankton that overwinters at depth. Some populations also migrate significant distances, moving between feeding grounds.

Long-Distance Migration: Individual basking sharks have been tracked traveling:

- From the British Isles to Newfoundland, Canada (nearly 6,000 miles/9,589 km)

- From New England to the Caribbean

- Across the Pacific Ocean between Asia and North America

- Between hemispheres (transequatorial migrations)

These migrations represent some of the longest documented for any shark species, rivaling the epic journeys of great white sharks.

Top Viewing Locations for Basking Sharks

If you want to see basking sharks in the wild, these locations offer the best opportunities during peak season (May-August):

Scotland:

- Inner Hebrides (Isle of Coll, Mull, Skye)

- Oban and surrounding waters

- Firth of Clyde

Ireland:

- West Cork

- Kerry Peninsula

- Cliffs of Moher region

England:

- Cornwall (Land’s End, Falmouth Bay, Penzance)

- Isle of Man

North America:

- Monterey Bay, California

- Bay of Fundy, Canada

- Cape Cod, Massachusetts

- Long Island, New York

Other Locations:

- Isle of Wight, UK

- New Zealand

- Southern Australia

Boat tours operate in many of these regions specifically for basking shark viewing, providing opportunities to observe these magnificent creatures in their natural habitat.

Lifespan and Reproduction: Life Cycle of Basking Sharks

The basking shark’s reproductive biology represents one of the least understood aspects of the species, though recent research has provided valuable insights into their remarkably slow life history.

Lifespan: How Long Do Basking Sharks Live?

Determining the lifespan of basking sharks presents significant challenges for researchers. Traditional aging methods used for other sharks—counting growth rings on vertebrae—produce inconsistent results for basking sharks, as the relationship between ring formation and annual aging remains unclear.

Estimated Lifespan: Most research suggests basking sharks live approximately 50 years or more, though some estimates extend to 30-70 years. The uncertainty stems from:

- Difficulty in aging large specimens

- Unclear growth ring formation patterns (may reflect growth episodes rather than annual cycles)

- Lack of long-term tagging studies tracking individuals throughout their entire lives

As one of the largest fish species with a slow growth rate and delayed maturity, basking sharks almost certainly possess relatively long lifespans compared to smaller shark species. Conservative estimates place their maximum age around 50 years, while some researchers suggest they might live considerably longer.

Sexual Maturity and Size

Basking sharks reach sexual maturity at surprisingly large sizes and advanced ages:

Males:

- Mature at lengths of 13-16 feet (4-5 meters)

- Estimated age at maturity: 6-13 years

- Mature at smaller sizes than females

Females:

- Mature at lengths of 16-20 feet (5-6 meters)

- Estimated age at maturity: 12-20 years

- Must reach substantially larger sizes before reproduction

This delayed maturity—particularly in females requiring nearly two decades to reach reproductive age—makes basking shark populations extremely vulnerable to overfishing, as individual sharks must survive many years before producing offspring.

Reproduction: Ovoviviparous Development

Basking sharks are ovoviviparous, meaning their eggs develop and hatch inside the mother’s body, with pups born live rather than as eggs. This reproductive strategy falls between egg-laying (oviparity) and live birth with placental connection (viviparity).

Gestation Period: Basking sharks have one of the longest gestation periods of any animal on Earth: 2-3.5 years. This extraordinarily lengthy pregnancy allows embryos to develop to large sizes before birth, ensuring pups are well-prepared for independent life.

During gestation, embryos likely practice oophagy (eating unfertilized eggs) or adelphophagy (eating less-developed embryos) for nutrition—a behavior documented in related shark species.

Litter Size: Estimated litter sizes are small: 1-6 pups, with most researchers suggesting an average of 2-4 pups per pregnancy. This low fecundity (reproductive rate) further contributes to the species’ vulnerability.

Pup Size at Birth: Basking shark pups are born at impressive sizes:

- Estimated length at birth: 5-6 feet (1.5-1.8 meters)

- Some estimates suggest newborns may reach 8 feet (2.4 meters)

These large birth sizes reflect the extended gestation period and ensure pups are large enough to avoid most predators immediately after birth.

Mating Behavior: Very little is known about basking shark mating behavior, as it has rarely been observed. Mating likely occurs during spring and summer months in coastal waters when sharks aggregate. Male basking sharks possess claspers (modified pelvic fins used for reproduction), but the actual mating process remains poorly documented.

Some females show bite marks and scarring that may result from mating encounters, suggesting males may grasp females during copulation—a behavior common in many shark species.

Reproductive Rate and Population Implications

The combination of:

- Delayed maturity (12-20 years for females)

- Extended gestation (2-3.5 years)

- Small litter sizes (2-4 pups)

- Long intervals between pregnancies (likely 2-4 years)

…creates an extremely low reproductive rate that makes basking shark populations highly vulnerable to overfishing and slow to recover from population declines.

A single female basking shark might produce only 10-20 offspring during her entire lifespan—far fewer than most fish species. This “K-selected” life history strategy (few offspring, high parental investment) worked well for millions of years in natural conditions but leaves the species vulnerable to human exploitation.

Basking Shark Teeth and Unique Anatomy

Despite their massive size and shark lineage, basking sharks possess surprisingly diminutive teeth and several other unique anatomical features adapted for their filter-feeding lifestyle.

Tiny, Non-Functional Teeth

Tooth Characteristics:

- Size: Only 5-6 mm (0.20-0.24 inches) in length—about the size of a grain of rice

- Shape: Conical, hooked, and curved backward

- Number: Hundreds of teeth arranged in multiple rows, with approximately 100 teeth per row

- Rows: Typically 3-4 functional rows in the upper jaw and 6-7 rows in the lower jaw

- Function: Essentially non-functional for feeding

These minuscule teeth stand in stark contrast to those of predatory sharks. A great white shark’s teeth, for comparison, can measure 2.5-3 inches (6.3-7.5 cm) in length—roughly 10 times larger than basking shark teeth.

Why Such Small Teeth? The basking shark’s tiny teeth reflect its evolutionary adaptation to filter feeding. Unlike predatory sharks that use teeth to capture, kill, and dismember prey, basking sharks have no need for large, serrated teeth. Their food consists of microscopic plankton that requires no chewing.

Possible Functions: Scientists speculate that basking shark teeth may serve non-feeding purposes:

- Possibly used during mating (males gripping females)

- Vestigial structures from predatory ancestors

- Minor role in sensory perception

The teeth’s hooked, backward-curving shape suggests they might help grip during mating, but this remains unconfirmed.

Gill Rakers: The Real “Teeth” of Filter Feeding

While the teeth are functionless, the basking shark’s gill rakers serve as the true food-capturing structures. These dark, bristle-like projections line the interior of each gill arch, creating a sophisticated filtering system.

Gill Raker Characteristics:

- Arranged in dense rows along each gill arch

- Create a fine mesh capable of trapping plankton as small as a few millimeters

- May be shed seasonally (subject of ongoing research)

- Essential for extracting nutrition from thousands of tons of water daily

The gill rakers work like a sieve: water flows in through the mouth, passes over the gill rakers (which trap plankton), then exits through the gill slits. The trapped plankton is periodically swallowed while the shark closes its mouth momentarily.

Massive Liver: Buoyancy and Energy Storage

The basking shark’s liver is one of its most distinctive anatomical features:

Liver Size and Composition:

- Accounts for 25% of total body weight

- Runs the entire length of the abdominal cavity

- Can weigh 2,000-2,500 pounds (900-1,100 kg) in large individuals

- Contains approximately 500 gallons of oil

Functions:

- Buoyancy Regulation: The liver is rich in squalene, a low-density hydrocarbon oil with a specific gravity less than water. This provides near-neutral buoyancy, allowing the shark to maintain depth without expending energy swimming.

- Energy Storage: The oil-rich liver serves as a long-term energy reserve, storing nutrients that can sustain the shark during periods of low food availability (winter months when plankton is scarce).

Historical Exploitation: The enormous, oil-rich liver made basking sharks valuable targets for commercial hunting. The oil was extracted and used for:

- Lamp oil (before petroleum products)

- Cosmetics

- Lubricants

- Vitamin A supplements (liver is vitamin-rich)

This exploitation drove massive population declines before protective regulations were implemented.

Other Unique Anatomical Features

Smallest Brain-to-Body Ratio: Basking sharks have the smallest brain-to-body weight ratio of any shark species, reflecting their relatively passive lifestyle. They don’t need the complex predatory instincts or rapid decision-making of hunting sharks, so their brains remain proportionally small despite their massive bodies.

Highly Textured Skin: The skin is covered in tiny, tooth-like structures called placoid scales (dermal denticles) and coated with a thick mucus layer. This rough texture can cause abrasions to divers who touch them, despite the sharks’ gentle nature.

Large, Laterally-Positioned Eyes: The relatively small eyes positioned on the sides of the head suggest vision is not the primary sense. Basking sharks likely rely more heavily on smell and electroreception to detect plankton concentrations and navigate their environment.

Strongly Keeled Tail: The crescent-shaped tail features a prominent lateral keel along the caudal peduncle (where the tail meets the body), providing efficient thrust for sustained, slow swimming.

Enormous Heart: While precise measurements are rare, the basking shark’s heart must be proportionally massive to pump blood through such an enormous body. The cardiovascular system must circulate blood through a body measuring 20-30+ feet in length.

10 Fascinating Basking Shark Facts

- They Can Breach Like Whales Despite their massive size and slow swimming speed of just 2-3 mph, basking sharks can leap completely out of the water in spectacular breaching displays. Scientists believe breaching serves multiple purposes: removing parasites attached to their skin, communicating with other sharks, or simply playful behavior. Witnessing a 10,000-pound shark launching itself skyward remains one of nature’s most stunning spectacles.

- Their Liver is Worth More Than Gold (Historically) A basking shark’s liver can contain up to 500 gallons of oil rich in squalene and vitamin A. During the peak of basking shark hunting in the mid-20th century, a single large shark’s liver could be worth thousands of dollars—making them more valuable pound-for-pound than many precious commodities. This unfortunately drove extensive hunting that decimated populations.

- They Filter Enough Water to Fill an Olympic Swimming Pool Every Hour A feeding basking shark filters approximately 2,000 tons (528,000 gallons) of water per hour—enough to fill an Olympic-sized swimming pool. Over a full day of feeding, a single shark might process 10-12 million gallons of seawater to extract sufficient plankton for survival.

- Record Aggregations: 1,398 Sharks in One Spot While typically solitary, basking sharks sometimes form massive aggregations. In November 2013, an unprecedented gathering of 1,398 basking sharks was spotted off the coast of New England within an 11-mile radius—the largest concentration ever recorded. Scientists believe exceptional plankton blooms attract these super-aggregations.

- Mistaken for Sea Monsters and Plesiosaurs Decomposing basking shark carcasses have repeatedly been mistaken for prehistoric sea monsters. The Stronsay Beast (1808, Scotland), the Zuiyo-maru carcass (1977, Japan), and other “globster” remains initially identified as plesiosaurs were later confirmed through DNA analysis to be basking sharks. The decomposition process removes the jaw and gill structures, leaving a long neck-like appearance that resembles extinct marine reptiles.

- They Have One of the Longest Pregnancies in the Animal Kingdom At 2-3.5 years, the basking shark’s gestation period ranks among the longest of any animal, competing with elephants (22 months) and sperm whales (16 months). This extraordinary pregnancy duration produces large, well-developed pups measuring 5-6 feet at birth—immediately capable of independent survival.

- They Dive Deeper Than Most Submarines While famous for surface feeding, basking sharks dive to depths exceeding 3,000 feet (900 meters)—deeper than most modern military submarines operate. These deep dives occur primarily during winter months when they feed on deep-water zooplankton, remaining active year-round rather than hibernating as once believed.

- Their Teeth are Smaller Than Your Pinky Fingernail Despite being the second-largest fish and a member of the shark family, basking sharks have teeth measuring only 5-6mm—about the size of a grain of rice. These hundreds of tiny, non-functional teeth contrast starkly with their massive 3-foot-wide mouths, reflecting their complete adaptation to filter feeding.

- They Can Travel Across Entire Ocean Basins Tagged basking sharks have been tracked making transoceanic migrations spanning thousands of miles. One individual traveled from the British Isles to Newfoundland—a distance of nearly 6,000 miles (9,589 km) across the Atlantic Ocean. These epic journeys rival those of great white sharks and demonstrate the species’ remarkable navigation abilities.

- Population Dropped 80% in Just 50 Years From the 1950s to the 2000s, global basking shark populations declined by an estimated 80% due to commercial hunting, bycatch, and boat strikes. This catastrophic decline led to endangered species protections in many countries and international trade restrictions. Today, populations are slowly recovering in some regions thanks to conservation efforts, though the species remains endangered globally.

Frequently Asked Questions About Basking Sharks

1. Are basking sharks dangerous to humans?

No, basking sharks are not dangerous to humans and have never been documented attacking people. These gentle filter feeders pose no threat despite their massive size. They feed exclusively on microscopic plankton and show no interest in humans or large animals. Basking sharks are typically docile and slow-moving, often allowing divers and boats to approach closely. However, their sheer size (up to 40 feet and 10,000+ pounds) and rough skin warrant respectful distance—accidental contact with their powerful tail or abrasive skin can cause injury, though this is never intentional aggression.

2. How big is a basking shark compared to a great white shark?

Basking sharks are significantly larger than great white sharks. An average adult basking shark measures 26 feet (7.9 meters) and weighs 9,300 pounds (4,200 kg), while an average great white measures 15 feet (4.6 meters) and weighs about 2,000 pounds (900 kg). This makes basking sharks approximately 1.7 times longer and 4-5 times heavier than great whites. The largest recorded basking shark (40.3 feet, estimated 36,000 pounds) dwarfs even the largest great whites (maximum 20 feet, approximately 5,000 pounds).

3. What is the difference between a basking shark and a whale shark?

Basking sharks and whale sharks are both massive filter-feeding sharks but differ significantly. Whale sharks are larger (up to 60+ feet vs 40 feet for basking sharks), have distinctive spotted patterns (basking sharks are solid gray-brown), and prefer tropical warm waters (basking sharks prefer temperate cool waters). Whale sharks have wider, flatter heads with terminal mouths, while basking sharks have pointed snouts with subterminal mouths. Basking sharks have enormous gill slits extending almost completely around their heads—a key identification feature whale sharks lack.

4. How long do basking sharks live?

Basking sharks are estimated to live approximately 50 years or more, though determining their exact lifespan remains challenging. Some research suggests maximum ages of 30-70 years, with 50 years being a conservative estimate. The uncertainty stems from difficulties in aging these large sharks—traditional methods of counting growth rings on vertebrae produce inconsistent results. As large, slow-growing fish with delayed maturity (females don’t reproduce until age 12-20), basking sharks almost certainly have relatively long lifespans similar to other large shark species.

5. Can you swim with basking sharks?

Yes, you can swim with basking sharks in certain locations where it’s legally permitted, as they are harmless to humans. Popular swimming and diving locations include Scotland’s Inner Hebrides, Cornwall (UK), Ireland’s west coast, and parts of California. However, regulations vary by region—some areas prohibit approaching within certain distances (often 10+ feet/3+ meters). When swimming with basking sharks, never touch them (their rough skin can cause abrasions), don’t block their swimming path, avoid chasing them, and maintain respectful distance. Many tour operators offer guided basking shark experiences during peak season (May-August).

6. Why are basking sharks called “basking” sharks?

Basking sharks are called “basking” sharks because they appear to be basking or sunbathing at the ocean’s surface. When feeding, these sharks swim slowly just below or at the surface with their dorsal fins and sometimes tails visible above water, appearing to leisurely float in the sun. However, this “basking” behavior is actually active feeding—the sharks are filtering plankton that concentrates in warm, sunlit surface waters where phytoplankton (which feeds the zooplankton) thrives. The name is somewhat misleading, as the sharks are working hard to extract nutrition, not relaxing.

7. Where can I see basking sharks in the wild?

The best locations to see basking sharks in the wild during peak season (April-August) include Scotland (Inner Hebrides, Isle of Skye, Oban), Ireland (West Cork, Kerry Peninsula), Cornwall and the Isle of Man in England, California’s Monterey Bay, Canada’s Bay of Fundy, Cape Cod (Massachusetts), New Zealand, and southern Australia. These regions offer boat tours specifically for basking shark viewing. Sharks are most commonly sighted during warm, calm, sunny days when plankton blooms near the surface. May through July represents the prime viewing season in Northern Hemisphere locations.

8. What do basking sharks eat besides plankton?

Basking sharks eat only plankton—they consume no other food sources. Their entire diet consists of microscopic zooplankton including copepods (tiny crustaceans), barnacle larvae, decapod larvae, fish eggs and larvae, small shrimp, krill, and other drifting invertebrates. Unlike whale sharks, which occasionally consume small fish, basking sharks are strict plankton specialists with anatomical adaptations (tiny non-functional teeth, gill rakers for filtering) that make eating anything besides plankton impossible. They must consume approximately 2,000 pounds of plankton daily to sustain their massive bodies.

9. Are basking sharks endangered?

Yes, basking sharks are classified as Endangered on the IUCN Red List (as of 2021), meaning they face a high risk of extinction in the wild. Global populations declined by an estimated 80% between the 1950s and 2000s due to commercial hunting for liver oil, bycatch in fishing gear, boat strikes, and slow reproductive rates. Their life history—delayed maturity (12-20 years for females), long gestation (2-3.5 years), small litters (2-4 pups), and long intervals between pregnancies—makes populations extremely slow to recover. Many countries now protect basking sharks, and international trade is restricted under CITES Appendix II.

10. How do basking sharks reproduce?

Basking sharks are ovoviviparous, meaning eggs develop and hatch inside the mother’s body before pups are born live. Mating likely occurs during spring/summer in coastal waters, though actual mating has rarely been observed. Females have an extraordinarily long gestation period of 2-3.5 years—one of the longest of any animal. During pregnancy, developing embryos likely consume unfertilized eggs for nutrition. Litters are small (estimated 2-4 pups), and pups are born at impressive sizes of 5-6 feet, immediately capable of independent survival. Females don’t reach sexual maturity until 12-20 years old and likely reproduce only every 2-4 years, contributing to the species’ endangered status.

Conclusion

The basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus) stands as one of the ocean’s most remarkable inhabitants—a gentle giant that combines massive size with a peaceful, plankton-based lifestyle. As the world’s second-largest fish, these filter-feeding sharks play crucial roles in marine ecosystems while captivating observers with their slow-moving grace and distinctive surface-feeding behavior. Despite facing significant threats from historical overfishing and ongoing conservation challenges, basking sharks continue to patrol temperate oceans worldwide, filtering millions of gallons of seawater daily through their extraordinary gill rakers. Understanding and protecting these endangered creatures requires continued research, habitat protection, and public awareness of their ecological importance and vulnerable status in our changing oceans.